|

|

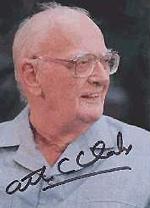

Clarke is the novelist whose vision underlay Stanley Kubrick's masterpiece, 2001: A Space Odyssey and made it synonymous with our deepest fears and hopes for the future. |

Arthur C Clarke relishes his 2001 |

| ||

|

A Space Odyssey, but not in 2001 |

Leaning forward in his wheelchair, the 83-year-old man speaks deadpan into the tape recorder: "Testing one, two, three. Testing. This is not Arthur Clarke, this is his clone."

As is so often the case with the grand old man of science fiction, it's a fantasy that might well be a reality in the years to come. A Houston-based company called Encounter 2001 has six strands from his thin gray hair and wants to launch Clarke DNA into space.

"One day, some super civilisation may encounter this relic from the vanished species and I may exist in another time," he muses. "Move over, Stephen King."

Clarke is the novelist whose vision underlay Stanley Kubrick's masterpiece, 2001: A Space Odyssey and made it synonymous with our deepest fears and hopes for the future.

Thirty-three years later, as humanity lumbers into the new millennium, he believes his visions of aliens, asteroids, paranoid computers and men on Mars may lie just this side of the moon.

Although he uses a wheelchair due to complications from polio he contracted in Sri Lanka in the 1960s, the 83-year-old Clarke looks more regal than feeble as he receives a visitor at his home in Colombo a few days before 2001 dawns. Barefoot in a blue Hawaiian shirt and coffee-coloured sarong, he has blended into the casual couture of his adopted South Asian homeland.

With his beloved one-eyed Chihuahua, Pepsi, at his heels, Arthur Charles Clarke is ever the eccentric soothsayer-scientist-philosopher, besieged by journalists seeking his reflections on 2001, and happy to oblige. 2001 belongs to him and the late Kubrick the way 1984 belongs to George Orwell, and he knows it.

It's hard to name any other author whose stories, essays and more than 50 novels have so adeptly combined futuristic fantasy with hard-nosed science, weaving implausible yarns in outer space that often turned out positively prescient.

In an article in Wireless World in 1945, he imagined satellites one day revolutionising global communications by relaying messages worldwide. The idea was so compelling that when the first satellites were launched in the 1960s, they could not be patented.

He once joked with CNN's Ted Turner that the media mogul owed him 10 per cent of his gross earnings.

Clarke's writings also foretold cellular phones, space stations, men on the moon and the Internet. There is no Hilton on the moon a la 2001, but there is one in Hanoi, which tells you just how hard it is to predict the future. Appearing at the height of the Cold War and America's involvement in Vietnam, 2001 envisaged something equally improbable: Russian and American astronauts on friendly terms.

As Clarke's famous dictum has it: "When a distinguished but elderly statesman states that something is possible, he is almost certainly right. When he states that something is impossible, he is very probably wrong."

Clarke wrote 2001 on a typewriter. Now, armed with half a dozen computers, he spends hours each day keeping in e-mail touch with friends, colleagues and fans.

"I don't know where half my friends are physically on the planet and it doesn't matter," he says.

The farm boy from England, whose accent still carries a Somerset burr, is Sir Arthur now, knighted in 2000 for his contributions to literature.

He became addicted to science-fiction after buying his first copies of the pulp magazine Amazing Stories at Woolworth's. He devoured English writers H.G. Wells and Olaf Stapledon and began writing for his school magazine in his teens.

Clarke then went to work as a clerk in Her Majesty's Exchequer and Audit Department in London, where he joined the British Interplanetary Society and wrote his first short stories and scientific articles on space travel.

With the Royal Air Force during World War II, Clarke became a radar officer who taught himself mathematics and electronics and conceived his earliest theories on geostationary satellites.

After the war, he got a degree in physics and mathematics at King's College, London. With the publication of the nonfiction The Exploration of Space in 1951, and the now-classic novel Childhood's End in 1953, Clarke's career rocketed.

Kubrick was interested in The Sentinel, a short story Clarke had written in 1948, about discovering an alien object on the moon - "a kind of burglar alarm, waiting to be set off by mankind's arrival."

From this emerged their jointly written screenplay for 2001: A Space Odyssey. Clarke simultaneously wrote the novel, fleshing out the story about a tribe of apes, a mysterious black monolith, a moon colony, a mission to the outer solar system and a devilishly soft-spoken computer named Hal 9000.

Hal decides that to fulfill the spacecraft's mission, he must prevent his own demise. So he calmly snuffs out astronauts one by one when he learns they intend to shut him down. This, and the lobotomy performed by Astronaut Dave Bowman on the computer, It is one of the most memorable sequences in the acclaimed movie.

The film and the novel came out a year before Neil Armstrong took that giant leap for mankind in 1969. Clarke had years earlier predicted it would happen by 1970.

He believes a space colony on the moon or Mars is not that far out. It's a matter of money and where to start. "Mars or the moon? I feel that we should establish ourselves on the moon and make our mistakes because that's only a couple of days away," says Clarke. "If anything goes wrong on Mars, it's nine months back."

Clarke also believes that computers with Hal's consciousness are not far off.

"There's a general feeling that computer intelligence will exceed man's at about 2010, 2020 or so," says Clarke. "The next question is when we will see the first conscious computers. When will the first computers say, 'I think, therefore I am?"'

Shouldn't this frighten mere mortals?

Yes, says Clarke, if computers ever develop the ability to defend themselves against being unplugged.

"If there's ever a war between man and machine," he says, "I can guess which side starts it."

He cocks an eyebrow and points to himself.

While 2001 dealt with artificial intelligence running amok, Clarke never joined the Y2K doomsday chorus. He credits everyday people with having taken the proper precautions.

And where millennia are concerned, Clarke is a purist who insists the new one doesn't start until January 1, 2001.

"It's a simple matter of fact," he says. "If you went to the grocer and you ordered 10 kilograms of sugar and then he set the scale at 1, wouldn't you feel that you'd been cheated?"

After 2001 he wrote 2010: Odyssey Two and 2061: Odyssey Three. At age 80 came 3001: The Final Odyssey. Will there be a 4001: The Absolute Final Odyssey ?

"Nope, nope. I don't have the energy or the attention span now to contemplate anything of that length," Clarke insists. "I've got far too many projects on my plate anyhow."

Kubrick died in March 1999, aged 70, but Clarke maintains a schedule that might seem daunting for an octogenarian who can no longer walk unassisted and must pause to take breaths.

Over the next six months, TV documentaries, awards, lectures, dedications and dozens of interviews are lined up. And he still finds the energy to play pingpong most evenings at the Colombo Swimming Club, "Leaning on the table and I can still beat up most of them."

He has no special plans for Jan. 1, 2001. "I will have a nap. It is a good excuse to have a good sleep," he says.

Clarke fell in love with the tropical island off the southern tip of India during a diving expedition in 1956 and never left. Life among Buddhists hasn't tilted him toward reincarnation.

"What's the input-output device and the storage mechanism?" the scientist in him asks. "Also," the philosopher chimes in, "if you're recycled and have no memory of other earlier lives, what's the point of it anyway?"

A theme throughout Clarke's novels is the evolution of the human spirit and man's innate desire to expand his reach. But he doesn't see religion as the answer. He calls religion a "disease of infancy," and in 3001: The Final Odyssey, it has become taboo, a product of man's early ignorance that provoked hatred and bloodshed.

"One of my objections to religion is that it prevents the search for God, if there is one." he says. "I have an open mind on the subject, if there's anything behind the universe. And I'm quite sympathetic with the views that there could be."

Clarke says his last ambition is to know whether there is intelligent life out there.

"It seems truly incredible if there's not. Nobody knows, but I would guess (the discovery) will happen this century as our technology develops. As our instruments become more and more sensitive, we may detect planets with oxygen."

Walter Cronkite of CBS asked Clarke during their joint narration of the Apollo 11 moon landing 31 years ago whether he would like to travel into space one day.

"I have every intention of going to the moon before I die," he replied then. Does he regret never having made it?

"Yes, but I feel I've gone into space so many times now," Clarke shrugs and grins. "You know - been there, done that."

Much of his work has dealt with immortality and humankind's drive to propagate and survive.

Yet Clarke, married and divorced long ago, says he does not regret having no children to advance his own genetics or spirit.

"I have all the fun and none of the responsibility," he says, referring to the three young women he watched growing up. They are the daughters of his Sri Lankan business partner and Australian wife who share his two-story mansion in Colombo and look after his health and the scuba-diving venture they run together.

"Those are my children, too, I guess," Clarke adds, pointing to his bookshelves filled with hundreds of editions of 2001: A Space Odyssey in dozens of languages.

And then there are the six hairs.